Medtronic Partnership to Help Guide Brain Surgeons

Project aims to develop personalized 3D brain images that assist neurosurgeons in the operating room.

Sometimes a project really is as complicated as brain surgery.

Researchers from Medtronic and the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are teaming up to create a new operating room system, powered by personalized 3D images, that may one day make it easier and safer for neurosurgeons to remove brain tumors.

“I’m really excited about this,” said Timothy Schaewe, a research engineer and the technical lead on the Medtronic side of the project. “This is a significant opportunity to take real steps forward in solving a clinical challenge and helping patients.”

Neurosurgeons already use 3D images and sophisticated navigation systems to guide them during brain surgery. Their goal is to remove tumors without affecting a patient’s speech, movement or other functions. But current imaging technology is limited. It can only show the brain’s anatomy, not the actual functions controlled by that area of the brain. It’s often difficult for surgeons to know precisely what brain functions will be affected by their incision.

“This is a significant opportunity to take real steps forward in solving a clinical challenge and helping patients.”

Timothy Schaewe, research engineer

That’s where this new brain-mapping partnership comes in.

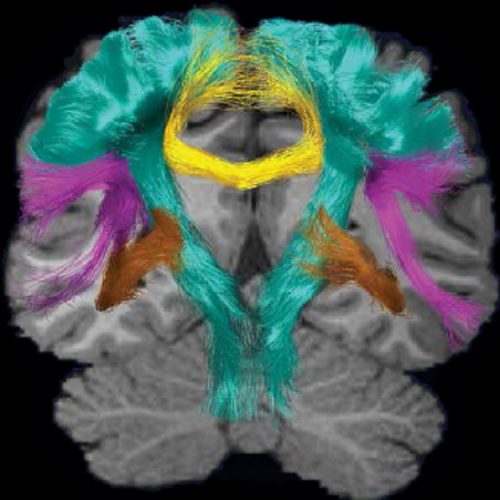

Washington University researchers have found a way to map a person’s brain functions, using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data. Called resting-state functional MRI (rsfMRI), the technique identifies specific brain functions through changes in blood flow. By combining that functional information with 3D images of the brain’s anatomy, and then incorporating it all into a Medtronic operating room system, researchers believe they can improve a surgeon’s ability to remove brain tumors, while lessening the risk of damaging brain functions in the process.

“We’re creating a software package that is going to combine our expertise in interpreting resting state data with the navigational technology at Medtronic, so that anyone who wants to use it to map functional areas, or to make a brain map for use in surgical planning, can have that readily available,” said Eric Leuthardt, MD, a professor of neurosurgery and of mechanical engineering and applied science at Washington University. “We think it will be a win-win situation.”

The five-year project, which started in January 2017, is funded through a grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes for Health (NIH).

The challenge for Schaewe’s team at Medtronic will be figuring out how to accurately display the data to doctors during surgery. It will be one of the biggest challenges of Schaewe’s 25-year career.

“Technology is finally reaching a point that allows us to do this,” he said. “We now can generate these personalized brain maps in a short time. It’s a matter of figuring out how to sort through and display all of this highly complex information. It will be complicated. But the potential for this is very, very high.”

It is, after all, brain surgery.