The Mom Test: Building High Quality Heart Valves

July 2017 - When it comes to building medical devices, details are everything. Because the finished product has to be good enough for Mom. “We have this thing we call the Mom test,” said Pa...

July 2017 - When it comes to building medical devices, details are everything.

Because the finished product has to be good enough for Mom.

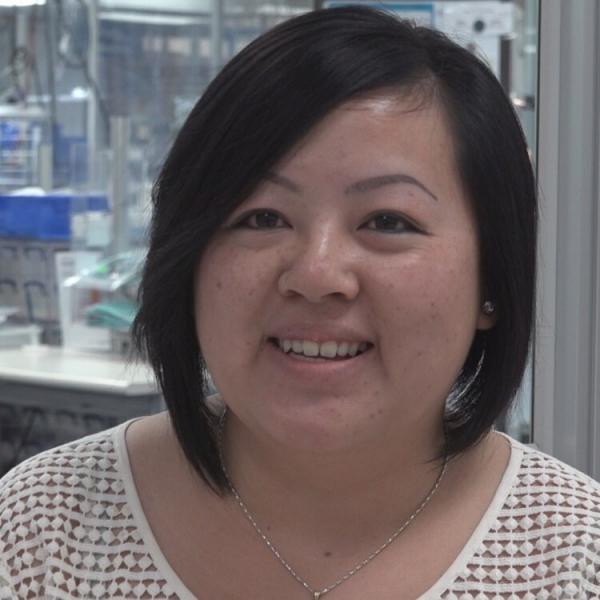

“We have this thing we call the Mom test,” said Pa Moua, a backup manufacturing lead at the Medtronic plant in Plymouth, Minnesota. “When I sew a carbon, in particular or assemble it together, I’m thinking to myself, ‘Do I, would I, put this in my Mom?’”

Pa and her colleagues build mechanical heart valves.

It’s a very detailed process.

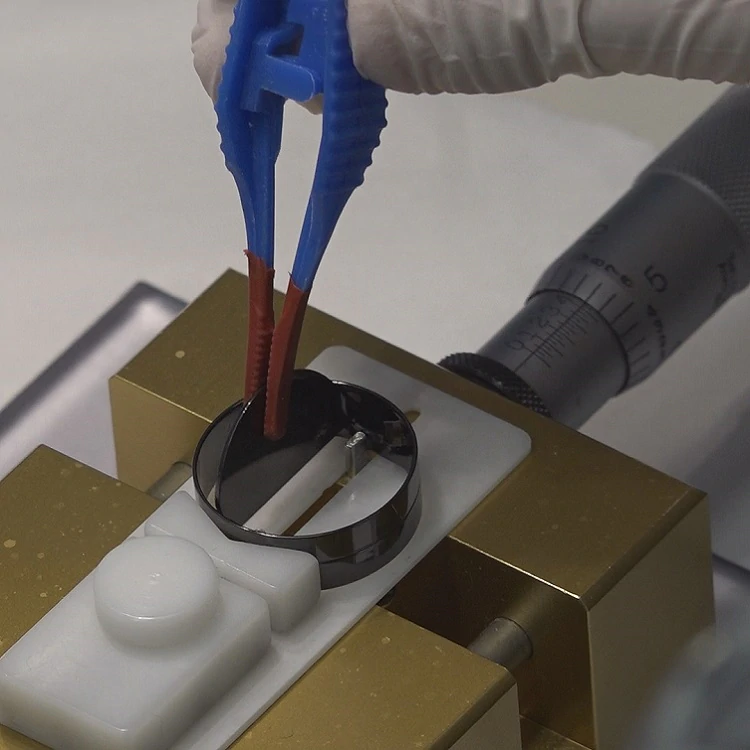

Graphite is first cut and shaped to very precise sizes.

Then it’s heated to more than 1,000 degrees Celsius, about the temperature of lava, and coated with carbon.

The valve is then sanded and polished, and fabric is sewed onto the outside of the valve ring. The valve is inspected multiple times throughout the process, before it’s eventually packaged and shipped.

Nearly 20 processes in all, until the finished valve is eventually implanted in a person’s heart.

A fact not lost on any of the people who work here.

“It always enters everybody’s mind I think,” said Lisa Towns, who polishes imperfections out of the valves. “You have to make it like you’re going to put it in yourself or your parents or your child,” she said.

Three years ago, the Plymouth plant set out to improve how it builds heart valves, through something called Cell Operating System, or COS.

“I like COS in particular because it helped the productivity of our team,” Pa said.

Pa was among the first participants in the plant’s conversion to COS.

She’s on a team – a cell – that sews fabric onto heart valves, so surgeons can then sew the valve into the heart.

She and her team analyzed videotape of their work. They scrutinized every stitch, every second, every move they made during the work day, looking to make things even a little bit better.

“Just doing the time study really helped,” she said. “How long does it take to thread a suture on? How long does it take to cut the suture?”

Using what they learned, Pa and her team recreated their workspace in cardboard, down to the smallest detail. Then they redesigned it and ran simulations, to see if their new ideas could work.

As a result of COS, Pa and her team now stand while working, rather than sitting and sewing for long periods. Ergonomics studies indicated that moving every 45 seconds is optimal for such work, and so COS built movement into their workflow.

They standardized the sewing process so that all team members now use the same and most efficient method of tying sutures.

And they overhauled the process, so that team members all work on different elements of the same valve until it’s finished, rather than working on parts in batches.

Three team members instead of five now finish more valves every day with fewer mistakes.

“We’ve seen a productivity improvement of over 30 percent,” said Jeff Livingston, the plant’s continuous improvement leader. “I’ve been here for 17 years and there are nuances that I learned through the process of converting to COS that I’d never thought about before.”

The Medtronic plant has converted three of the mechanical valve processes over to COS. In each case, teams increased the first-time quality yield of valves produced by as much as 18%. And productivity also increased, varying from 19% in one cell to 44% in another.

The Plymouth site is in the process of evaluating efficiencies in converting the rest of its valve processes to COS.

Other Medtronic COS teams, in places like Shanghai, Ireland and Mexico have seen similar results.

Yield, productivity, efficiency, and most importantly, measurements of product quality are all up significantly.

“Ultimately it benefits the patient,” said Jim Rhinhart, production group lead. “Whether it’s us getting product out the door quicker so doctors have the parts they need when they need them, or whether it’s building better quality into the part,” he said.

In addition, COS teams get time every week to talk through problems, or dream up even newer ideas for their workspace. If they identify issues they know they can create and test potential solutions.

“We just basically tear down everything and rebuild the whole thing over again,” said Ia Xiong, clean room supervisor. “You can experiment with anything. You can create anything you want and we will try as a support team and as a supervisor to provide the operators with what they need to make what they come up with work.”

The ultimate goal of COS is to build continuous improvement into how Medtronic makes such life-changing medical devices, like heart valves.

“Because it could be anybody else’s Mom. Their Dad, brother, sister, their kids,” Pa said.

If it’s going to be good enough for Mom, details are indeed everything.